Easter Birdwatching Observations: Insights from The Coopers

Share

Sunday 12th April 2020

Easter, but it doesn’t feel like it because of the personal, national and global concern about Covid-19 and growing number of deaths. However, as the Queen said in her Easter message “Easter isn’t cancelled; indeed, we need Easter as much as ever”.

This morning, as we are doing everyday at present, we read John’s (handwritten) diary from 1970 when we were first living in Kenya. On this day, 12th April, fifty years ago, we started by examining, sedating and treating an augur buzzard and we finished (after a trip to the Nairobi National Park) by visiting friends who were hand-rearing two young cheetahs. All part of the life of a vet in East Africa.

How different things seem half a century later! Today we are indoors or sitting in our tiny garden in Norfolk, England. No augur buzzards (although Margaret spotted a common buzzard in the sky above the house last weekend) and certainly no cheetahs! But plenty to interest and enthral the Armchair Naturalist. Insects are active in the sunshine, mainly bees and wasps and hoverflies. One of particular interest, easily identified by its long forward-pointing rigid proboscis (“tongue”) is the dark-edged bee fly (Bombylius major) which hovers like a helicopter over flowers in the garden.

We (Margaret) found it very difficult to photograph this bee fly before it flew off elsewhere. Its long proboscis doesn't show in this picture because it's underneath the bee fly in a flower. Can any Armchair Naturalist reading this get a better picture (of their own, not from the internet!)

Bee flies are delightful to watch, but their habits are rather less tasteful. They are parasites: they lay their eggs in the nests of other insects – namely the so-called ‘solitary mining bees’. These look rather like honeybees but are much smaller. They get their name from their habit of “mining” in sand or earth. The queen mining bee digs a tunnel and lays eggs in it; with the eggs she puts a ball of pollen and honey as food for the larvae. After this she emerges and dies.

We’ll tell readers more about bee flies and other mimics in a forthcoming podcast, when we shall also discuss the many sources of information that are available to Armchair Naturalists about our native animals and plants.

It’s been an exciting week for us two Norfolk Armchair Naturalists. On Tuesday 7th, at exactly 11:57am, we saw our first swallow – a single one, which flew speedily over the house at a height of about 30 metres. On the same day we noted our first holly blue butterfly, the species of “blue” that is most likely to be observed in gardens or through the window in towns because they lay their eggs (appropriately) on holly leaves.

On Thursday we had a short (government-sanctioned) walk for exercise. We rejoiced in the sight of many wild flowers, including cowslip, ground ivy, yellow archangel, tansy, a species of speedwell, violets and dandelions (Figures). The blackthorn was still in bloom (Figure). We heard our first chiff-chaff (Phylloscopus collybita), the one migrant warbler that most people will recognise because its call reflects its common (English) name. Another welcome sign of spring!

Ground ivy – part of a carpet of low-growing wild flowers. On the left is a red dead-nettle.

Tansy – similar to, but different from, dandelion

Margaret on our walk, with blackthorn and (bottom right) white dead-nettle

And what about butterflies? Which species have you Armchair Naturalists spotted so far this year? Our tally is small – brimstones, small tortoiseshells, a “white” (probably a female orange tip) in the distance, holly blues and so far only one peacock. The magnificent picture below of a peacock (Figure), on a wallflower, is from our friend David Alderton, another life-long Armchair Naturalist, who points out that it is an individual that has emerged from a winter’s hibernation. Only a handful of British butterflies hibernate: the other 50-odd species overwinter as eggs, larvae or pupae. The life cycles of insects in this country depend very much on the seasonal temperature changes.

A peacock butterfly (photo courtesy of David Alderton)

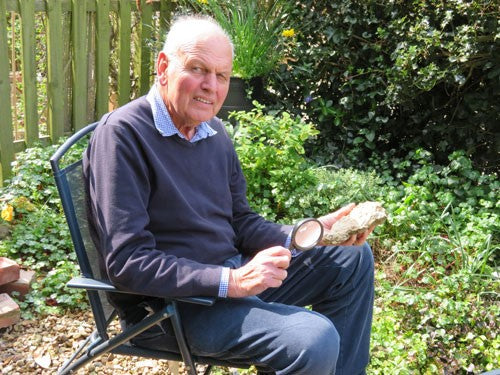

There is something timeless about stones and rocks and the Armchair Naturalist recognises these as part of the “living” world. They are, literally, the building bricks of our planet and they remind us of the history of the earth and its animals and plants. Fossils are a particularly obvious example of what we can learn from looking at rocks. The photograph of John below, a picture rather unkindly termed by Margaret “the two old fossils”, is an example (Figure). Note how a magnifying glass (hand-lens) can be used to look carefully at fossils, in this case at least three species of shell (Figure), as well as to examine insects, plants, feathers and animal tracks and signs. To the Armchair Naturalist everything is of interest and worthy of study.

Examining the specimens (“the two old fossils”)

At least three species of shell; the age of such widespread molluscs depends on the stratum in which they were found

Written by The Coopers